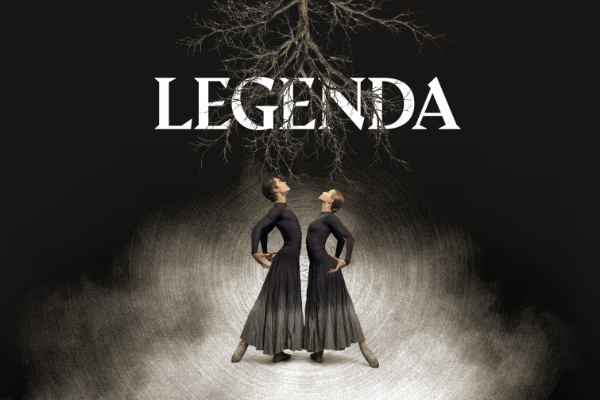

Stabat Mater / Le sacre du printemps

A double bill of dance performances

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PERGOLESI Stabat Mater (with live music)

Choreographer Edward Clug

Assistant Choreographer Gaj Žmavc

Music Director and Conductor Tomas Ambrozaitis

Set and Costume Designer Jordi Roig

Lighting Designer Tomaž Premzl

IGOR STRAVINSKY The Rite of Spring (with pre-recorded music)

Choreographer Edward Clug

Assistant Choreographer Gaj Žmavc

Set Designer Marko Japelj

Costume Designer Leo Kulaš

Lighting Designer Tomaž Premzl

One of Europe’s most prominent contemporary dance creators, choreographer and artistic director of the Ballet Company at the Slovenian National Theatre Maribor, Edward Clug—renowned worldwide for his abstract, minimalist contemporary ballet language and unexpected, provocative interpretations of the classical repertoire—returns to the Klaipėda stage with two ballets created at different times for different companies. The Rite of Spring was staged with the Slovenian National Theatre Maribor Ballet under his direction in 2012, while Stabat Mater was commissioned and premiered at the Gärtnerplatz State Theatre in Munich in 2013. In 2014, both ballets were combined in Maribor, becoming the company’s signature program, touring numerous ballet festivals and theatres worldwide, and receiving several revivals. “Both performances are related through the central figure of a woman and her incredible power of acceptance,” Clug reveals. “I do believe that the ability to embrace one’s fate and power arising from such acceptance is more in the nature of women. In case of Stabat Mater, the mother has to accept a sacrifice of her son on the cross, while in The Rite of Spring the maiden chooses to be sacrificed and accepts herself as a victim. It is interesting to follow the journey of these two different stories over the length of one evening.”

In his Stabat Mater, the choreographer engages in a resolutely modern – delicate and yet somewhat ironic – dialogue with Giovanni Battista Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater, a masterpiece of the Italian Baroque. Written in the last few weeks before the composer’s death in 1736, this tremendously expressive score for soprano, alto, strings and basso continuo is the setting of a 13th-century Christian hymn Stabat Mater dolorosa (“the sorrowful mother was standing” in Latin). According to one version, the Latin poem is attributed to the Franciscan friar, Jacopone da Todi. Once he was a wealthy nobleman who gave away all his possessions and became a wandering ascetic, after his wife was killed in an accident, for which he held himself indirectly responsible. Thus, the hymn about the suffering of the Blessed Virgin Mary, standing at the cross and mourning her crucified son, was written as a penitence for his worldly and greedy life.

A note from the choreographer: “It was neither my wish, nor idea to choose Pergolesi for this performance; it came as part of the commission. At first, I thought it was impossible to dance to Pergolesi’s music, so I decided to focus on the text, which remained the same over the centuries and in numerous settings. I had to find a way not to treat Pergolesi but to find the right theatrical environment that would frame my vision of his music. Together with set designer Jordi Roig, we came up with these very simple, clean and at the same time effective frames and images, directly referring to but not exactly retelling the biblical story of crucifixion. In one of the scenes, you can almost sense the aggression of a man against a woman, which resonates with the life of the author of this religious poem. But I did this intuitively, without having any knowledge of the story behind the text. On the other hand, when listening to Pergolesi’s music I became increasingly intrigued by his treatment of the text. Of course, the music, as we know it, is so striking, powerful and painful. But there are some arias in the Stabat Mater that convey some sort of joy or even happiness, which stand in complete contrast to the text portraying the Blessed Virgin’s sorrows. It made me understand that in a deeper, metaphysical sense the piece is more likely a sound depiction of hope and solace than of the pain and suffering. It also provoked me to reflect on life in all its dimensions, including almost humorous aspects in everyday life of contemporary women and men.”

________________________________________

“Edward Clug […] has achieved the near impossible: a new and meaningful interpretation of Stravinsky’s Le sacre du printemps,” wrote Maggie Foyer of the Dance Europe magazine after the premiere of Clug’s production in Maribor in 2012. Co-produced with the Maribor, European Capital of Culture 2012, the new production was an artistic tribute of the Maribor Ballet to Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971), honouring the 130th anniversary of composer’s birth. Additionally, the project raised the curtain for the centennial of the world premiere of Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring), which was celebrated around the globe in the year 2013. It is a well-known fact that Igor Stravinsky’s Le sacre du printemps, written for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and choreographed by Vaslav Nijinski, stirred up one of the greatest theatrical scandals of the 20th century at its première in Paris in May 1913. It was not ballet’s usual fare until well into the century: the old-line ballet critics and audiences regarded a possibility to watch The Rite of Spring “as more of an affliction than a privilege.” While the more progressive artists regarded it as a token of revolt against the hackneyed forms of art and a catalyst for change and new forms of artistic expression.

A note from the choreographer: “The Rite of Spring is undoubtedly a 20th-century masterpiece of cult proportions. It does not just represent a turnabout in Stravinsky’s own musical poetics, but also in the history of music. Furthermore, the entire evolution of the 20th century dance performativity is reflected in The Rite, starting with Nijinski’s original choreography and onwards, especially in Maurice Béjart’s majestic aestheticism and Pina Bausch’s unique creativity and lust for life. The latter two ‘principles’ have become a distinctive paradigm of the 20th century in their own right, influencing the majority of all subsequent staged choreographies. This ballet became an initiation into Stravinsky’s music for me as well when I was in my teens at the ballet school and had not the slightest dream of choosing a choreographer’s career one day. My interpretation of The Rite could also be perceived as a personal tribute to Nijinsky, to austere hermetism and ‘disturbing’ avant-garde character of his choreography whose infamous (lack of) ‘success’ has indeed become a dynamic platform for modern dance in the course of the 20th century. This interpretation of The Rite follows the original libretto and structure, which both depict a legend from pagan (pre-Christian) Russia. The legend conveys a story about the ritual sacrifice of a (virgin) maiden who has to dance to death, in order to restore fertility of the Earth, and regain the benevolence of the pagan spring deity. We have also preserved some iconographic details of the original production, such as women with long braids and rosy cheeks, and men with full-grown beards. On the other hand, I was looking for my own voice in this century-long saga of The Rite. I was thinking about the symbols that would encapsulate the work’s idea in modern ways but at the same time remain archaic, like the depicted pagan rites. While listening to the “Dance of the Earth” that closes the first part of the ballet, I felt an urge to have something heavy falling from above. We tried to experiment with water and it suddenly became evident that it is this element that gives meaning to the archaic rites of cleansing and consecration of the Earth, which prepare the soil for new life. In fact, there is one essential difference from the original libretto in my interpretation: The Chosen One is present on the stage from the very beginning of the performance, instead of appearing at the very end. That way we can watch the development of her character, witness her transformation: how she gets isolated from the community, taunted and attacked without remorse. But at the same time it is emphasized that the choice is in her hands because she perceives her sacrifice as a necessary means to salvage her community. This dual feeling: the fear of losing herself and pride in her role as a saviour. Again, she is thus enabled by the power of acceptance.”

AWARDS

Mask of Gratitude (27/3/2022) to the creative team for the best theatre performance of the year 2021 in Klaipėda

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710–1736)

STABAT MATER (1736)

for soprano, alto, strings and basso continuo

1. Duet: Stabat mater dolorosa (Grave)

Stabat mater dolorósa / At the Cross her station keeping,

juxta Crucem lacrimósa, / stood the mournful Mother weeping,

dum pendébat Fílius. / close to her Son to the last.

2. Soprano aria: Cujus animam gementem (Andante amoroso)

Cuius ánimam geméntem, / Through her heart, His sorrow sharing,

contristátam et doléntem / all His bitter anguish bearing,

pertransívit gládius. now at length the sword has passed.

3. Duet: O quam tristis et afflicta (Larghetto)

O quam tristis et afflícta / O how sad and sore distressed

fuit illa benedícta, / was that Mother, highly blest,

mater Unigéniti! / of the sole-begotten One.

4. Alto aria: Quae moerebat et dolebat (Allegro)

Quae mœrébat et dolébat, / Christ above in torment hangs,

pia Mater, dum vidébat / she beneath beholds the pangs

nati pœnas ínclyti. / of her dying glorious Son.

5. Duet: Quis est homo (Largo) – Pro peccatis suae gentis (Allegro)

Quis est homo qui non fleret, / Is there one who would not weep,

matrem Christi si vidéret / whelmed in miseries so deep,

in tanto supplício? / Christ’s dear Mother to behold?

Quis non posset contristári / Can the human heart refrain

Christi Matrem contemplári / from partaking in her pain,

doléntem cum Fílio? / in that Mother’s pain untold?

Pro peccátis suæ gentis Bruis’d, / derided, curs’d, defiled,

vidit Jésum in torméntis, / She beheld her tender child

et flagéllis súbditum. / All with bloody scourges rent.

6. Soprano aria: Vidit suum dulcem natum (Tempo giusto)

Vidit suum dulcem Natum / For the love of His own nation,

moriéndo desolátum, / Saw Him hang in desolation,

dum emísit spíritum. / Till His spirit forth He sent.

7. Alto aria: Eja, Mater, fons amoris (Andantino)

Eja, Mater, fons amóris / O thou Mother! fount of love!

me sentíre vim dolóris / Touch my spirit from above,

fac, ut tecum lúgeam. / make my heart with thine accord.

8. Duet: Fac ut ardeat cor meum (Allegro)

Fac, ut árdeat cor meum / Make me feel as thou hast felt;

in amándo Christum / Deum make my soul to glow and melt

ut sibi compláceam. / with the love of Christ my Lord.

9. Duet: Sancta mater, istud agas (Tempo giusto)

Sancta Mater, istud agas, / Holy Mother! pierce me through,

crucifíxi fige plagas / in my heart each wound renew

cordi meo válide. / of my Savior crucified:

Tui Nati vulneráti, / Let me share with thee His pain,

tam dignáti pro me pati, / who for all my sins was slain,

pœnas mecum dívide. / who for me in torments died.

Fac me tecum pie flere, / Let me mingle tears with thee,

crucifíxo condolére, / mourning Him who mourned for me,

donec ego víxero. / all the days that I may live:

Juxta Crucem tecum stare, / By the Cross with thee to stay,

et me tibi sociáre / there with thee to weep and pray,

in planctu desídero. / is all I ask of thee to give.

Virgo vírginum præclára, / Virgin of all virgins blest!

mihi iam non sis amára, / Listen to my fond request:

fac me tecum plángere. / let me share thy grief divine.

10. Alto aria: Fac ut portem Christi mortem (Largo)

Fac ut portem Christi mortem, / Let me, to my latest breath,

passiónis fac consórtem, / in my body bear the death

et plagas recólere. / of that dying Son of thine.

Fac me plagis vulnerári, / Wounded with His every wound,

fac me Cruce inebriári, / steep my soul till it hath swooned,

et cruóre Fílii. / in His very Blood away;

11. Duet: Inflammatus et accensus (Allegro ma non troppo)

Inflammátus et accénsus, / Be to me, O Virgin, nigh,

per te, Virgo, sim defénsus / lest in flames I burn and die,

in die iudícii. / in His awful Judgment Day.

Fac me cruce custodiri Christ, / when Thou shalt call me hence,

Morte Christi praemuniri be / Thy Mother my defense,

confoveri gratia. / be Thy Cross my victory;

12. Duet: Quando corpus morietur (Largo assai) – Amen… (Presto assai)

Quando corpus moriétur, / While my body here decays,

fac, ut ánimæ donétur / may my soul Thy goodness praise,

paradísi glória. / Safe in Paradise with Thee.

Amen. Amen.

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

THE RITE OF SPRING (1913)

Pictures of Pagan Russia in Two Parts

Part I: The Adoration of the Earth

Introduction

Augurs of Spring

Ritual of Abduction

Spring Rounds

Ritual of the Rival Tribes

Procession of the Sage: The Sage

Dance of the Earth

Part II: The Sacrifice

Introduction

Mystic Circles of the Young Girls

Glorification of the Chosen One

Evocation of the Ancestors

Ritual Action of the Ancestors

Sacrificial Dance